|

|

Next Previous Table of content2. Artificial feelings

The most famous emotional computer is probably HAL

9000 from the movie "2001 - A Space Odyssey" by Stanley Kubrick. It was a

shock for many people to see a vision of an artificial intelligence equal,

if not superior, to humans. But much more fearsome was that this machine

had emotions, too, which led finally to the destruction of

all humans aboard the spaceship. It was probably no coincidence that one of the

advisors to Stanley Kubrick was Marvin Minsky, one of the fathers of

Artificial Intelligence. For Minsky, an emotional computer is a thoroughly

realistic vision:

Nowadays, al lot of AI researchers accept the fact

that emotions are imperative for the functioning of an "intelligent"

computer. This insight does not stem from a deep reflection over the topic

but rather from the failures of classical AI. The new catchphrase,

therefore, is not AI, but AE - artificial emotions. As well as the idea of an intelligent computer, the

idea of an emotional computer constitutes for most people more of a threat

than of a hopeful vision. On the other hand, such a concept holds a

strange fascination. It is no coincidence that emotional machines play an

important role in the popular culture. Take "Terminator 2", for example. In James Cameron's

movie, the Terminator is a robot without any

feelings who learns to understand human emotions in the course of the

story. There is even one scene in which it looks like he is able to

experience an emotion itself, though the director leaves us speculating if

this really is the case. Another example is the robot from "No. 5 lives"

which changes from a war machine into a "good human". Robots are, at least in popular culture, often

described as strange beings whose character is mainly threatening. This is

a trait they share with "true" aliens. Remember Star Trek's Mr. Spock, who

only seems to know logic but no feelings, like all inhabitants of his home

planet, Vulcan. But in many episodes we come to see that even he cannot

function without emotions. And even "Alien", the monster from the films of the

same name, terrifies us by its ferocity and its malicious intelligence,

but underneath it harbours at least some rudimentary feelings, as we can

see in the fourth part of the series. It could be concluded thus that a strange

intelligence becomes really threatening for us humans only then if it

has at least a minimum of emotions. Because if it consisted only of pure

logic, its behaviour would be predictable and finally controllable by

humans. No surprise, then, that emotions finally have found

their way into Artificial Intelligence. MIT's Affective Computing Group

describes the necessity to develop emotional computers as follows:

Although the works of Damasio are quite recent, this

position is not new but can be traced back to the 1960s. However, it has

been forgotten - at least by most AI researchers. The utter inability of

computers to execute complex activities autonomously has revived interest

in this approach. Where in the past the emphasis of AI research lay with

the representation of knowledge, this has now changed to the development

of "intelligent autonomous agents". The interest in autonomous agents results from

practical requirements, too. Take space exploration, for example: Wouldn't

it be great to send robots to faraway planets which can autonomously

explore and react, because a remote control would be impractical or

impossible over such a distance? Or take software agents which would be

able to autonomously sift through the internet, decide which information

is of use to their "master" and even change the course of their search

independently? Franklin and Graesser define an autonomous agent as

follows:

According to this definition, autonomous agents can

be implemented as pure software - something which is hotly debated by a

number of researchers. Brustoloni (1991) for example defines an autonomous

agent as a system that is able to react appropiately and in real time to

stimuli from a real, material environment in an autonomous and

target-oriented way. Pfeifer (1996), too, believes that a physical

implementation is a indispensable condition for an autonomous agent,

especially if it should have emotions. His four basic principles for a

real life agent according to the "Fungus Eater" principle are: a)

autonomy The agent must be able to function without human

intervention, supervision, or direction. b)

self-sufficiency The agent must be able to keep itself functioning

over a longer period of time, i.e. to conserve or fill up its energy

resources, to repair itself etc. c)

embodiment The agent must have a physical body through which it

can interact with the physical world. This body is especially important:

d)

situatedness The agent must be able to control all its

interactions with its environment itself and to let its own experiences

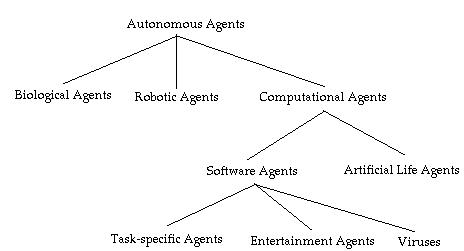

influence this interaction. A taxonomy for autonomous agents as proposed by

Franklin and Graesser (1996) makes clear that autonomous agents of all

kinds are not fundamentally different from humans: Fig.

1: Taxonomy of autonomous agents (Franklin and

Graessner, 1996, p. 7) The demand for a physical impementation has led to a

closer co-operation between robotics and AI. Individual aspects of the

principles have already been realized through this co-operation, but there

exists no implementation of a complete system which would be sufficient

for all the described requirements (at least not one that I know of). Despite the increased interest in autonomous agents,

the attempts to create intelligent machines so far must be regarded as

failures, even if, for example, Simon (1996) is of a different opinion.

Franklin (1995) outlines the three substantial AI

debates of the last 40 years, which arose in each case from the failure of

the preceding approaches. It stands without doubt that these failures advanced

the development of intelligent machines, but, as Picard (1997) points out,

there ist still a substantial part missing. And this part are the

emotions. It is interesting that the increasing interest in

emotions in the AI research has a parallel in the increasing interest of

cognitive psychology in emotions. In the last decades, emotion psychology

never had the center stage but was relegated to the sidelines. This is

changing considerably, certainly aided by recent discoveries from the

neurosciences (see e.g. LeDoux, 1996) which attribute to the emotional

subsystem a far higher importance for the functioning of the human mind

than assumed so far. A further parallel can be observed in the increasing

interest in the topic "consciuousness". This discussion was also carried

primarily from the circles of artificial intelligence, the neurosciences

and philosophy into psychology. A cursory glance at some of the

substantial publications shows, however, that the old dichotomy between

cognition and emotion continues here: Almost none of the available works

on consciousness discusses emotions. This is the more astonishing because the fact is

undisputed that at least some emotions cannot exist without consciousness.

Specifically all those emotions which presuppose a conception of "self",

for example shame. One does not need to know the discussion around

"primary" and "secondary" emotions to state that there are emotions which

arise independently of consciousness; but likewise emotions, which

presuppose consciousness.

Next Previous Table of content

|

|